BOM Sniffing to XSS

Table of Contents

In this post, we will learn about text encoding, how browsers determine content encoding, talk about BOM and finally how we can bypass DOM sanitizers by just playing around with input encoding.

For those interested, this post is based on an interesting challenge called Secure Notes which was authored by @13x1 and have appeared in the recent GPN 2024 CTF.

We are given 16 lines of source code and access to an admin bot.

Let’s see:

In summary, this is a barebone Node http server that has three routes:

/: a submittable text form/submit?<content>: saves<content>undernotes//notes/<id>: returnsnotes/<id>.htmlcontents

You can attempt this before moving on, just npm i dompurify jsdom, then node app.js and you are set.

Getting Started⌗

I hope you gave it a go, now with the solution.

I will be providing a walkthrough-like explanation of the ideas required to solve this challenge as we go so we can maximize learning.

First, let’s patch our server so we can have better clarity on how’s our input looking like internally at various stages:

For context, and for each of the following payloads we will be sending them and capturing the

idof the saved note using the following scaffold:

We need the note_id since that is what we provide to the admin bot in case of successful XSS.

Endianness⌗

Let’s start by seeing how the server behaves with different payloads:

For starters, we can see DOMPurify kick in and effortlessly sanitize our payload. The sanitized payload is then encoded and saved as little endian UTF-16 or utf-16le as JS calls it.

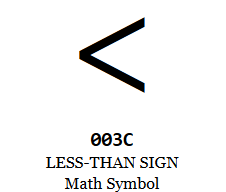

utf-16le is a variable length encoding with a minimum codepoint length of two bytes or 16-bits. Each codepoint is stored in little endian order. For example, the ASCII character < (0x3c) will be represented as \x3c\x00 in utf-16le.

You can see how the buffer looks like in the example above, since our payload is restricted to ASCII, the utf-16le encoded payload ends up being a null byte delimited sequence of ASCII characters.

Note: The python codec for little endian UTF-16 is called

utf-16-le, the aliasutf-16lealso works as per the docs .

Let’s try to encode our payload in utf-16-le and see what happens:

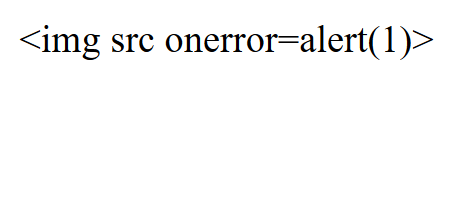

The browser receives the byte sequence annotated as data above and because it has been instructed using the response’s Content-Type: application/html; charset=utf-16le, it will decode the data as utf-16le and retrieve exactly the DOMPurify sanitized input:

<img src onerror=alert(1)>

which is rendered to a literal:

Notice that in this second example, onerror=alert(1) was completely preserved, compared to the first one where DOMPurify removed it. In both instances, DOMPurify did what is necessary to neutralize the input. In the first case, the payload was a valid HTML tag that would have resulted in malicious code execution through onerror, hence DOMPurify had to strip that attribute.

In this instance however, the input to DOMPurify was utf-16le encoded already, that is DOMPurify received a null byte delimited ASCII string similar to this (but using 0x00 instead of spaces):

< i m g s r c o n e r r o r = a l e r t ( 1 ) >

Our UTF-16LE encoding broke the payload, turning it into a plain text string that we can no longer use for XSS. The only thing that DOMPurify will do though, is HTML entity encode the < and > to < and > so that they can be displayed correctly by the browser.

We need to rethink our strategy.

We need a payload that meets these two conditions:

- When read by

DOMPurifyis considered benign - When saved by the server as little endian, the browser can still evaluate it as XSS

Our UTF-16LE encoded payload above meets step 1 as it is considered benign by DOMPurify, however, it IS actually benign and does nothing when loaded.

What about UTF-16 utf-16-be? Let’s try:

Data received, sanitized and saved by the server is exactly the same as it’s little endian counterpart, perhaps the leading null byte is stripped at some point either by DOMPurify or by the http server, not sure.

The exact reason is irrelevant since regardless of where exactly was the leading null byte stripped, the result will be the same, we are getting a string of null byte delimited ASCII characters that is completely benign and produces the same result:

More Than Just Text⌗

What if we flip the bytes?

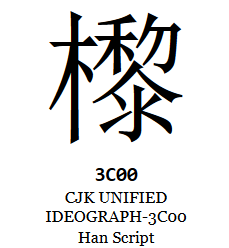

The Unicode codepoint \u003c when interpreted as big endian, will give us the character equivalent to 0x3c = 60 = "<" while the same sequence, interpreted as little endian will give us the character equivalent to 0x3c00 = 15360 == "㰀". This is critical for solving this challenge.

To demonstrate:

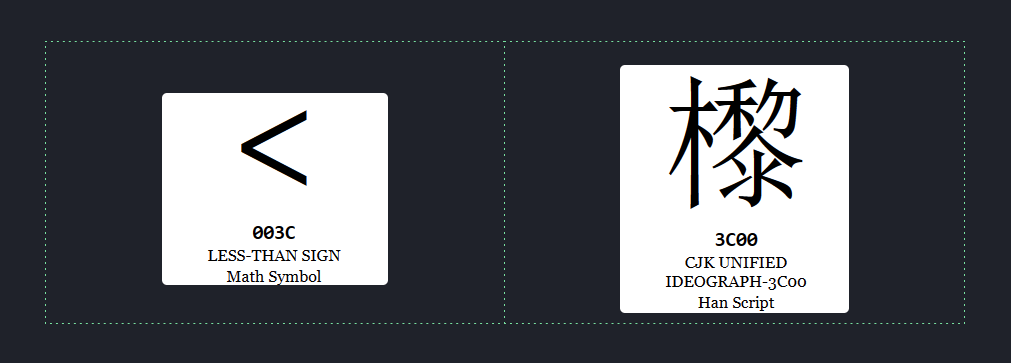

|  |

|---|

The figure above shows us both codepoints next to each other, one is a special HTML character that signals the start of a tag (0x3c) while the other is a CJK character (0x3c00) that has no meaning, well at least to an HTML parser :)

In internationalization, CJK characters is a collective term for graphemes used in the Chinese, Japanese, and Korean writing systems - Wikipedia

Let’s try and make use of our new information:

In our updated payload, we encode our payload using utf-16-be then decode it back into Python’s internal UTF-8 representation using utf-16-le. This has the effect of swapping the bytes of our payload and using UTF-8 (Python’s internal string representation) as our method storing the swapped bytes.

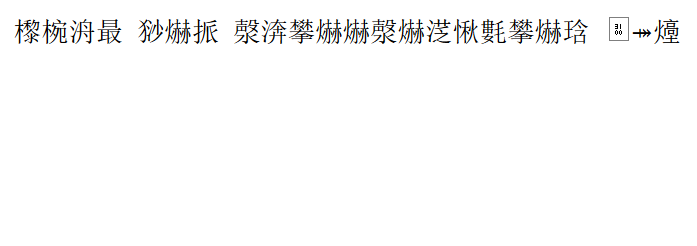

Printing out the swapped UTF-8 bytes in Python we get ‘‘㰀椀洀最 猀爀挀 漀渀攀爀爀漀爀㴀愀氀攀爀琀⠀⤀㸀" notice the first character, looks familiar?

When this string goes through DOMPurify, it will mostly be a passthrough as it is just a pure CJK string with no HTML meta characters, it is then saved in little endian and decoded by the browser also as little endian, the user ends up seeing the same CJK string:

We need to do better. Hmm…

Let’s stop and recap what we have done. So far, we are able to disguise our payload by swapping each byte pair using our little .encode('utf-16-le').decode('utf-16-be') trick. This method allowed our payload to go through DOMPurify since it really is just an innocent string at that point.

However, can we get this innocuous string to do something malicious on the client side?

Looking closely, what we managed to pass through is not just any random string. It is unique as it actually holds double meaning based on the way you choose to interpret it, one way being less innocent than the other.

What does that mean?

As we know, the server responds with Content-Type: application/html; charset=utf-8 which instructs the browser to treat the response as little endian, this in turn causes our manipulated, swapped bytes like \x00\x3c to be decoded to correctly to 㰀 instead of being rendered as the malicious form that we intend.

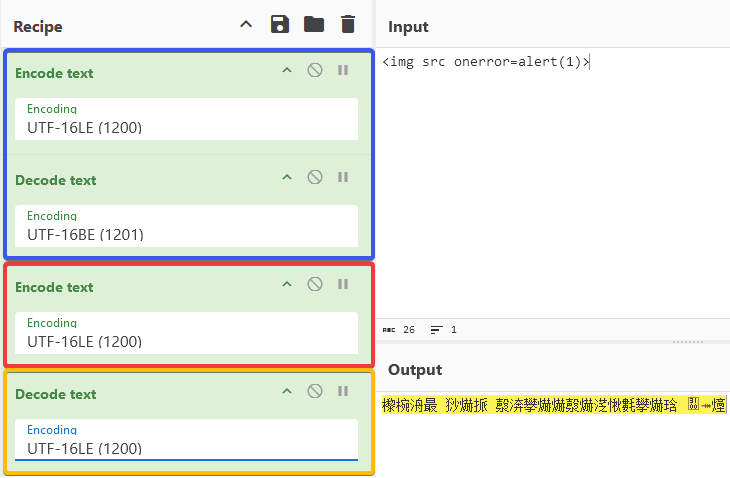

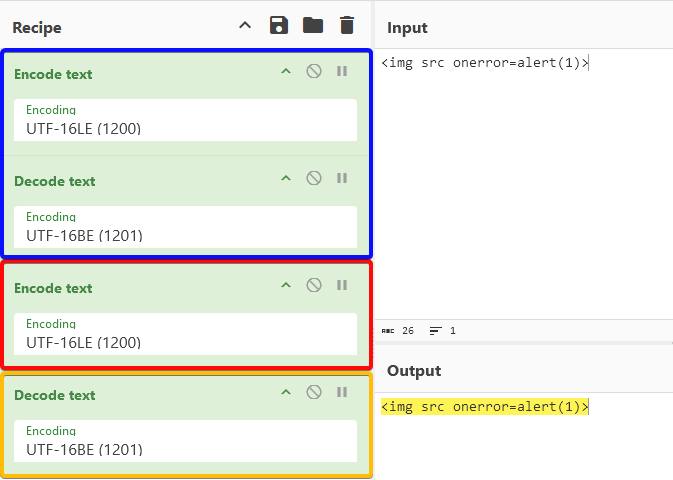

We can illustrate this better in CyberChef:

- Blue is us swapping the payload bytes into a harmless string

- Red is the server as it encodes and saves the DOMPurify output to disk

- Orange is what the browser sees - also a harmless string in the case of UTF-16LE

Let’s see what happens if we change the orange part to interpret the string as UTF-16BE:

The illustration above means that if we could, somehow, instruct the browser to ignore that charset=utf-16le in the response and use utf-16be instead, we will be able to achieve XSS.

BOM… BOM… BOM…⌗

Our findings above, lead us to one question: how does our browser determine content encoding or endianness of its content to start with?

I chose to ask the most authoritative source on the matter, the WHATWG HTML specification itself.

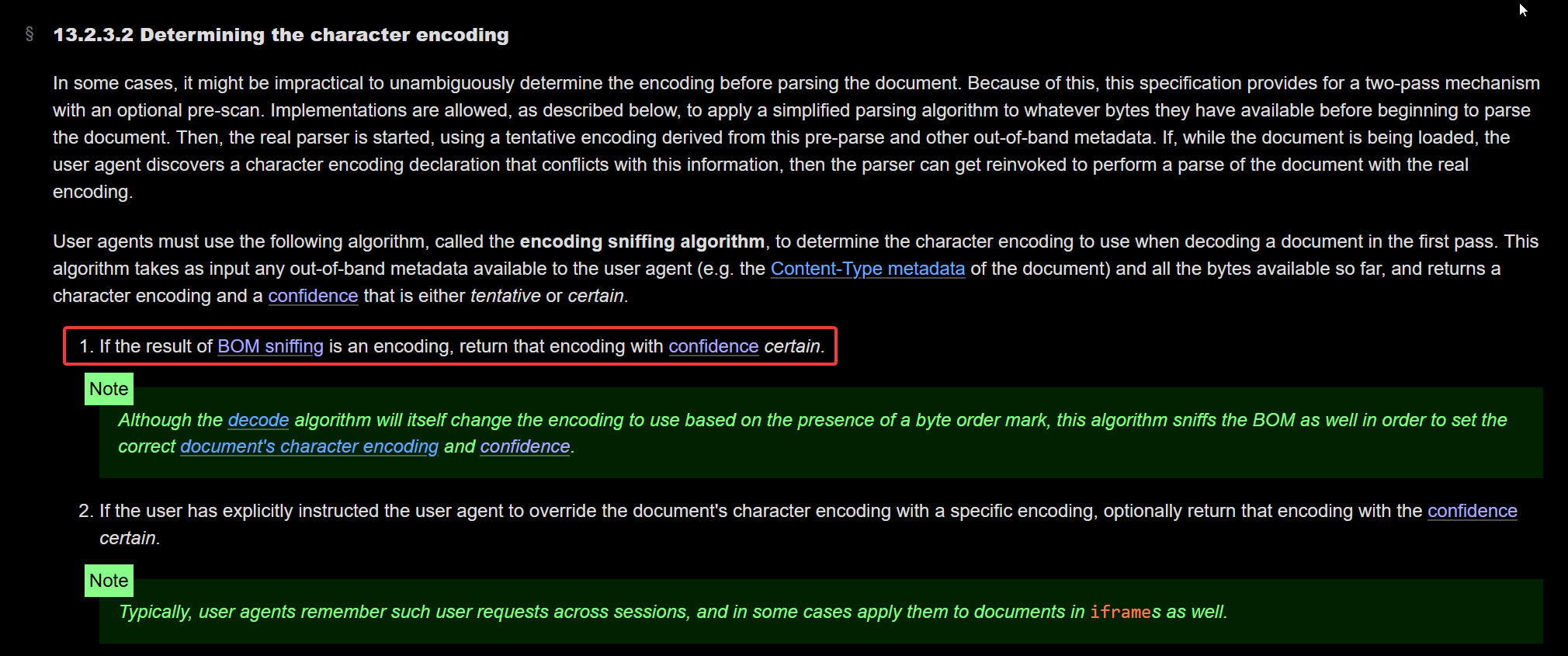

Within the WHATWG HTML Standard we can search for “encoding” or “charset” and eventually we can find a section that reads “Determining the character encoding” :

The section lists 9 different algorithms for determining a document’s character encoding, ordered by precedence, primarily:

- If the result of BOM sniffing is an encoding, return that encoding with confidence certain.

So there is a procedure called “BOM sniffing” that takes precedence over everything else for determining the character encoding of a document.

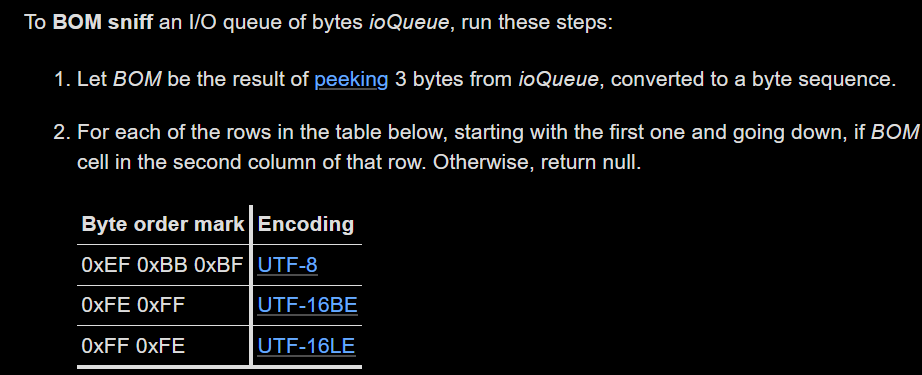

Let’s see what the section on BOM sniffing has to say:

Reference

Reference

Byte order mark (BOM) sniffing is a technique that allows a parser to determine the character encoding and endianness of the content by inspecting the first two to three bytes for a certain sequence.

The sequence used as a BOM is the U+FEFF ZERO WIDTH NO-BREAK SPACE codepoint which is an invisible zero-width Unicode codepoint. This codepoint’s encoded represntation is used as a telltale regarding the encoding of the rest of the content.

| Byte order mark | Encoding |

|---|---|

| 0xEF 0xBB 0xBF | UTF-8 |

| 0xFE 0xFF | UTF-16BE |

| 0xFF 0xFE | UTF-16LE |

Notice that if we are to use Python to send this sequence, we should use the \ufeff escape literal or the b'\xef\xbb\xbf\ byte sequence since Python uses UTF-8 strings. In Python, \ufeff is not equivalent to \xfe\xff as the former would be UTF-16BE decoded to fe ff as a single codepoint, while the latter would be UTF-16BE decoded to 00 fe 00 ff as two codepoints.

The example below illustrates that the two are indeed different using three encodings:

Play around with encoding and decoding, try different combinations until you get the hang of it, it is useful to wrap your head around this important concept and be able to write code that deals with encodings comfortably.

As a side note, you can use util.unicode.org to explore different codepoints and their representations.

Assembling the Pieces⌗

Based on everything we have discussed so far, we know that to coerce the browser into using UTF-16BE encoding, we need to provide the Byte order mark 0xfe 0xff before our payload. we also know how to send the BOM correctly:

Looks good on paper, let’s wrap it all in a nice script and run it:

Internally:

Which also means:

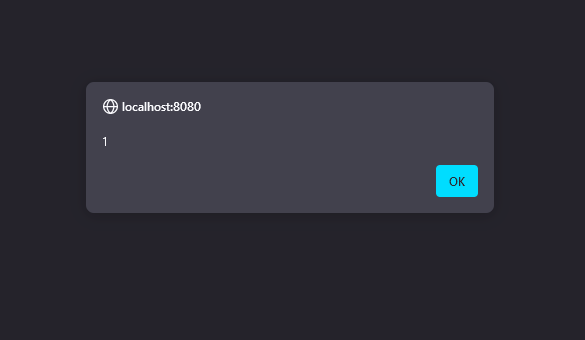

We can now craft a weaponized payload to send the admin:

Running this on the challenge instance, and sending the saved note_id to the admin bot gives us:

GPNCTF{UN1C0D3_15_4_N34T_4TT4CK_V3CT0R}

A neat vector indeed.

Well, that was fun and educational. Generally, I find encoding and Unicode fascinating and would like to learn more about them, I don’t know why actually, I used to think of encoding as a dull topic, but as I explored it more, the challenge it tries to solve, how different encodings are more suitable for certain applications, parsing logic, etc, I realized it actually is very interesting.

Also now that I know that encoding can be abused to perform various web attacks like WAF bypasses and even the XSS we have done here, I am more interested than ever :)

References:

- https://docs.python.org/3/howto/unicode.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unicode

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/UTF-8

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unicode_Consortium

Anyways, hope you enjoyed - I did - and learnt something new - I also did - and see you in the next one! 👋